Some memories of Ingemar Lindh by Tor Arne Ursin

The first time I heard about Ingemar Lindh was during the first sessions of the International School of Theatre Anthropology (ISTA) in November 1980. I had participated in the first month long session in Bonn. Now the whole artistic staff of ISTA were in Holstebro while I was in Norway preparing a four day symposium which I was arranging with my company, Grenland Friteater.

I got a call from Peter Elsass, one of the Odin Theatre’s closest collaborators, who was at the session in Holstebro: ‘There is this guy down here that you got to bring to Norway’, he said, ‘He is the missing link!’

‘What do you mean?’, I replied. (I was quite confused). Peter went on – ‘He is the missing link between the orient and the west – between the west and the codified oriental theatres. He is doing a demonstration of corporal mime, the Western equivalent to the Eastern approach to acting. You gotta bring this guy to Norway! He is already booked for ISTA in Stockholm. His name is Ingemar Lindh. Can you find the money?’

It was not like we really had that money, but Peter Elsass was quite convincing. And if there was a missing link between traditional oriental acting and our western group theatre, it would be really helpful. We had been struggling for a month in Bonn trying to find it.

The day after I spoke with Trond Hannemyr, my collegue from Grenland Friteater who was in Holstebro for the symposium as an observer.

‘Yeah’, he said ‘there is this guy here who is helping out in the kitchen and looking really tired and miserable. I thought he was just the dishwasher, but then Eugenio made one of his long speeches to introduce the world’s best and most interesting demonstration of corporal mime, and in came the dishwasher! He threw away the towel and made the best acting demonstration ever. I don’t understand much of the relevance to us of what Sanjukta is doing, but this guy explains it all. Plus he is really funny!’

We found the money and we brought Ingemar to Porsgrunn for the first time for the ISTA symposium in November 1980. Peter and Trond were quite right. He made a very good demonstration of Decroux mime, of the geometrical principles, the «triple design» and the figure work of Decroux, of which he was a true master. And he was very funny!

Late on Friday night I was called to a meeting with Eugenio in his hotel room about the future of our theatre company which, despite the huge success of the conference, was falling apart. Nobody else knew, but in reality it was only me left in the group. Eugenio started off by saying he thought I should give up directing, but ended up wishing me good luck with the next project. – ‘I don’t understand a word you are saying’, he told me, ‘but I am sure it will be a good performance’. He then generously promised to talk to my actors to convince them of continuing, and to set up a series of workshops with pedagogues from the Odin and Grotowski’s Teatr Laboratorium. And with Ingemar Lindh!

At the last night party Eugenio grabbed Ingemar with both arms and grinned: – Now, old Ingemar! You are coming up here again to do a workshop with these young people! – ‘Oh, I don’t know…’, Ingemar responded timidly. But it was a deal.

The day after I drove Eugenio, Ingemar and Toni Cots to the airport in Oslo. Eugenio sat beside me for the two hour drive. He was as joyful and energetic as ever and full of stories of his secret life in Scandinavia when he first came here in the nineteen-fifties. From time to time I looked in the rear view mirror. Toni and Ingemar were asleep even before we came out of town. Toni from five days of hard work, Ingemar from years of struggle, I imagine.

I could sense how miserable he was at the time, but I didn’t know the reasons until much later. His company, the Institutet för Scenkonst (Istituto di Arte Scenica) had split up and at the same time he had separated from his girlfriend and long-time partner. And as always, he was broke. The Odin Theatre took him in. They were long-time friends and colleagues. Ingemar stayed in Holstebro, working and giving classes for the young actors at the Odin. actors like Julia Varley, Francis Pardeilhan and Silvia Ricciradelli.

Ingemar’s workshop would be the first one during 1981, then we would have Torgeir Wethal from the Odin in the summer and Ryszard Cieslak and Rena Mirecka from the Teatr Laboratorium in late fall. I asked for a title for the poster and publicity work and Ingemar decided on «Stener å gå på» (Stepping stones, Pietre di Guado), which later became the title of his book based on the notes from the seminar.

Ingemar’s ten-day workshop with us was scheduled for April 1981. In the meantime we made plans for our new performance project based on hard-boiled American detective fiction. Being an apprentice director, Eugenio assigned me one of his oldest collaborators, Torgeir Wethal, as my mentor. Within the rules of our special world of avant-garde theatre, Torgeir was friendly, patient and understanding, yet insistent and quite merciless with his questions of the actor’s craft. It was a perfect match for me. Torgeir came for a few days in December and we worked with training and improvisation. I sucked in the information.

After new year 1981 I gathered the company of four actors for work on training and improvisations to collect materials for the performance work. I used what I had learned from ISTA and from Torgeir. The physical training was hard – hours of acrobatics, exercises from Kathakali and composition work. The most exciting part was the improvisation. We worked on how to distinguish what was organic and true in individual improvisations and how to fix and repeat what we wanted. I started working on the montage of bits of improvisations, but I didn’t really get anywhere. I ran up a huge telephone bill making international calls every evening to Torgeir in Holstebro trying to find a way forward.

By the time Ingemar came in the beginning of April, we were a strong and disciplined group ready for the next step. Well, more than ready! And we had gathered a nice bunch of participants for the workshop – some acting students and other young actors and dancers, mostly from Oslo. Spring had just come and Ingemar seemed a lot more joyful now than he had been in the gloom and darkness of Scandinavian November. There was a glimpse of a joke in his eyes.

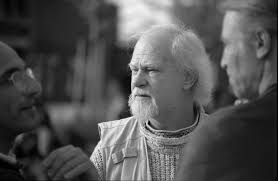

I realize now that he was just thirty-six at the time, but he looked much older. I was fifteen years younger, but the difference could just as well have been fifty. Ingemar had that quality of the wise man, the sage, that special quality which makes you lean forward and listen even if he speaks in a low voice.

He suggested from the outset that we should document the whole seminar, so we brought the small radio/cassette deck with a built-in microphone that we had in the office together with some empty tape cassettes. He said;

‘You are a generation that cannot do the old theatre, because it is dead to you – to us. We are compelled to seek a new theatre’.

And with these words we embarked on a ten day journey from which there has been no return for me and my colleagues. The workshop was an explosion of energy and creativity. Ingemar led us methodically through all the steps that would eventually make up the different chapters in his book «Stenar att gå på»:

- A physical training that prepares for the creative moment. How to make the first step onto the floor a step in the direction of the performance?

- What is improvisation? What is a personal theme? How to use improvisation to collect personal materials for a performance score through variation and development of physical themes.

- What is a meeting? How to integrate social situations as a key element of training and improvisation work.

- The power of silence. Isometric work and action in time rather than space.

- Voice as an extension of the body and the power from physical actions.

- Recreating, rather than repeating mechanically, complex moments of a group improvisation.

- Integrating materials «from without» into the improvisation work: Texts, music, props, scenography.

- Incarnating the personal themes and scores.

Workshop in Porsgrunn 1981. Elsa Kvamme, Trond Hannemyr, Anne-Sophie Erichsen, Martin Slaato, Lars Vik, Per Borg, Ida Fredriksen m.fl.

Probably the members of Grenland Friteater got much more out of the workshop than the rest of the participants. We had been well prepared for it through our ambitions and struggles to make a performance like nobody had seen before. Ingemar untied the knots for us. Simply told, he set us free.

We continued to work. A few weeks after the workshop we had created most of the materials that would make up our performance «The Play Is Over», the first production we would tour with throughout Europe.

Ingemar came back once during the spring. He worked with us on the performance material and we discussed how to proceed with the book project from «Stener å gå på». Although sometimes difficult, we had noted down everything that had been said during the workshop. Together we revised the script, making it into a scrapbook where what happened inside the work space was contrasted with notes of global and local, everyday events during the same days. We had contacts within Oslo University Press and set up a meeting. The editors said they wanted Ingemar to change the script into a ‘proper’ book and gave him 30 000 kroner in advance to finish it.

Those were days of tremendous energy. In Grenland Friteater we felt stronger than ever. The four actors – Eva, Lars, Lars Steinar and Trond – had turned into five with the addition of Geddy, who had stayed on after the workshop and entered straight into the performance work. In June 1981 we started making public work demonstrations with the performance material.

During the next eighteen months we would go on to become colleagues and friends not only with Ingemar, but with the whole group of Institutet, who were getting together again in the winter of 1982. It so happened that the two groups met many times that year. We saw each other in Denmark, and in festivals in Spain and Italy, making a string of public improvisations together under the title «Leaving Theatre». These were made possible because of the common techniques of group improvisation. To use the last words of dialogue from our performance The Play Is Over: «- I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship».

But that is yet another story.

I think anybody who had the experience of working with Ingemar would agree he was a brilliant pedagogue. But did that make his theories of acting and theatre correct? Is it possible at all to separate the man from the theories?

As I mentioned earlier, Ingemar had the appearance of the sage, even if he was quite young when we met; the thin hair, the scruffy beard, the bad skin (probably related to an inherited heart condition) and the deep set eyes. Ingemar also had the very rare gift of being able to incarnate and master many physical techniques and disciplines and at the same time present the theories and philosphy of the arts: Corporal mime, Grotowski-technique, Kung Fu, to mention just a few.

At the time we met, I remember thinking that some of his strength must come from the fact that he came from ‘the other side’ of the modern theatre revolution of the nineteen-sixties and seventies. He had experienced the old theatre and been part of the rebellion against it. He had been part of posing the questions that led to the techniques and theories that were transmitted to us in the next generation. He knew what key questions had provoked what was taught us as results. That was a whole lot of difference. Thinking of it now, I would say that he was more than ‘twice born’.

He had started out as a traditional ballet dancer, training at the Academy of Ballet in Stockholm, but this was not enough for him and he went to Paris to study corporal mime with Etienne Decroux. He stayed three years, during a period which I imagine must have been one of the most creative and fruitful in Decroux’s career. When Decroux later came to the Odin Theatre for a Scandinavian workshop (in 1968, or perhaps 69), it was Ingemar who assisted and translated. Decroux always remained Ingemar’s true master, even if he left the daily practice of the mime for periods of time. Decroux’s theories of theatre were always the foundation of Ingemar’s work.

He had started out as a traditional ballet dancer, training at the Academy of Ballet in Stockholm, but this was not enough for him and he went to Paris to study corporal mime with Etienne Decroux. He stayed three years, during a period which I imagine must have been one of the most creative and fruitful in Decroux’s career. When Decroux later came to the Odin Theatre for a Scandinavian workshop (in 1968, or perhaps 69), it was Ingemar who assisted and translated. Decroux always remained Ingemar’s true master, even if he left the daily practice of the mime for periods of time. Decroux’s theories of theatre were always the foundation of Ingemar’s work.

But during the years in France, some of the students of Decroux encountered the work of Jerzy Grotowski, from the very first time Grotowski came to France together with Ryszard Cieslak to do workshops. Ingemar told me in private conversations of how Grotowski was very interested in the theatre of Decroux because of the obvious relationships to his own. In 1997 Zygmunt Molik very clearly told me that the ensemble of the Teatr Laboratorium had been studying a ‘manual’ of Decroux’s work while they were still in Poland and developing the exercises plastiques, but I have never been able to confirm this information from other sources.

Ingemar participated in a month-long workshop in Provence (or perhaps Aix or Avignon) where Grotowski and Cieslak taught the plastiques and the physical exercises. He told me that one day the Polish masters had to leave in a hurry for a couple of days for a meeting in Paris. Ingemar asked in bewilderment: ‘But who is going to lead the training work then?’ Grotowski responded him immediately: ‘You can do it! You know all the work!’ Grotowski must have had an immediate trust in Ingemar. I think he was the first one in the west to be shown this confidence.

During ‘Stener å gå på’ (1981), the technical starting point for the work as a version of the physical series which was very much developed from the Grotowski series. This emphasised explosions from the lumbar region and giving a much more ‘nervous’ and ‘electric’ dynamic than the hatha yoga-based fluidity of the Grotowski series.

I think this series was developed by Ingemar together with actors from the Odin and Ingemar’s own company Studio 2 during their long stay in Holstebro in the late sixties and beginning of the seventies. But the Odin actors quickly took these exercises in a different direction whereas Ingemar kept the exercises in what looks to me to be a more original form. This also applies to the plastiques. I have worked on the plastiques with many different masters and in 1981 also with Ryszard Cieslak, who took part in developing them, but Cieslak was very reluctant to teach them. I have never come across anyone who on one hand could demonstrate the exercises of Grotowski and at the same time could analyze and explain the theory of them in the same way as Ingemar. In this he was the true master.

Now, soon twenty-five years since Ingemar’s death, another line of thought strikes me. Ingemar’s theatre was truly an actors’ theatre in the sense of the roots of the word actor – that is, the one who acts. This is not in opposition to a dancers’ theatre, but maybe in opposition to a directors’ theatre – to the theatre in the sense of the Gesamtkunstverk.

Meeting with new generations of dancers during the last years, I rather find that their attitude towards and conciousness of the art of the stage often corresponds much more with Ingemar’s line of thought then most theatre practitioners. The focus is on the art of the performer, not the literary context of the performance. To this end I wonder if it is true to say that the kind of experiences and ways of thinking of Ingemar are better represented today within the dance community than within that of the theatre.

Ingemar’s last public performance, as far as I know, was a lecture he gave in Porsgrunn during the international theatre festival here in June 1997. The topic was ‘Art vs. Creativity’. The auditorium was packed, which was unusual for this kind of occasion. We even had to change the venue to get room enough for everyone who wanted to attend. There might be several reasons for this, but an obvious one is the great impact the work of Ingemar and the institute had had on more than one generation of theatre groups, many of them Scandinavian. Quite a number of these groups were gathered in Porsgrunn for the 1997 festival, and the curiosity for Ingemar’s teaching was widespread amongst the festival community.

I owe a lot to Ingemar. I owe a lot to many people in the theatre community, not least my collegues in Grenland Friteater for sharing my experiences through forty years, and to Eugenio Barba and the Odin for introducing me to him. These are things that would need their own essay to explain.

Ingemar is the only one I would call my master.

Not only did he unknowingly come to my rescue at a crucial point in my career, he also gave me the role model for a director and the relationship between actors and director which was different from the norm of nineteen-seventies group theatre, that of a strong hierarchy and a clear division between actors and directors. It was often talked about how different the experiences and mind-sets of actors and directors were. Directors who thought they could jump onto the stage and swap roles with the actors were often ridicule – by Ingemar too. I remember one night in Pontremoli when I got really irritated over this and raised my voice in protest. But Ingemar countered immediately: ‘But I don’t mean you, Tor Arne! You always followed the training.’

I guess there is also something very Scandinavian about this interpretation of the role. Ingemar was not only Swedish, but from a working-class background in Gothenburg – city of shipbuilding and car manufacturing and one of the most internationally orientated cities in Scandinavia. We had lots in common.

But like always in life, there is something inexplicable. Just like in art. What is creation? How do we achieve it – time and again? Nobody – to my knowledge – could guide one closer to the answer to these mysteries than Ingemar Lindh.

Søndre Sandøy, primo October 2020

Many thanks to Andy Smith for helping me with the language.